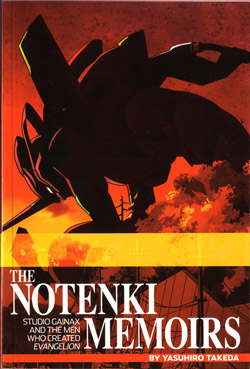

The Notenki Memoirs: Studio Gainax and the Men Who Created Evangelion

When I heard that this book was being released in English by ADV Manga, I immediately knew I had to get it. I consider myself a fan of Gainax, and I've always been interested in its history, especially the company's pre-Evangelion days, which is what the book focuses on (less than one full page is spent talking about post-Eva Gainax works). As it turns out, The Notenki Memoirs by Yasuhiro Takeda (originally published in Japan in 2002) was exactly the book I was looking for.

When I heard that this book was being released in English by ADV Manga, I immediately knew I had to get it. I consider myself a fan of Gainax, and I've always been interested in its history, especially the company's pre-Evangelion days, which is what the book focuses on (less than one full page is spent talking about post-Eva Gainax works). As it turns out, The Notenki Memoirs by Yasuhiro Takeda (originally published in Japan in 2002) was exactly the book I was looking for.In case you were wondering, "Notenki" refers to Takeda himself. Back in the early 80's, some of the fans who would eventually form Gainax made amateur films. One such film, Kaiketsu Notenki, featured Takeda as Notenki, the hero of the story. Because of that, many people still humorously refer to Takeda as Notenki.

Yasuhiro Takeda (pictured right, with a Daicon III cosplayer) is currently the General Manager of Gainax. That title is a bit elusive, however, as is Takeda's actual role in the company. In a company as freewheeling as Gainax, job titles have traditionally not meant very much. People just did whatever was necessary to keep the company going and to finish whatever projects were going on. (Oftentimes, poor management led to projects not being completed, but you can read about that in the book.) In a nutshell, Takeda is one of the top administators of Gainax, and more importantly, he has been involved with the company from the very beginning, even in the days before Gainax was officially incorporated in December of 1984.

Yasuhiro Takeda (pictured right, with a Daicon III cosplayer) is currently the General Manager of Gainax. That title is a bit elusive, however, as is Takeda's actual role in the company. In a company as freewheeling as Gainax, job titles have traditionally not meant very much. People just did whatever was necessary to keep the company going and to finish whatever projects were going on. (Oftentimes, poor management led to projects not being completed, but you can read about that in the book.) In a nutshell, Takeda is one of the top administators of Gainax, and more importantly, he has been involved with the company from the very beginning, even in the days before Gainax was officially incorporated in December of 1984.Gainax has always been known as an otaku-centric company--by fans for fans. It's part of their public persona, such as portrayed through Otaku no Video, the anime whose plot is loosely based on the origins of Gainax itself. Takeda's book delves into the fannish origins of the now legendary company. In great detail, Takeda explains the climate of science fiction and anime fandom in late 70's Osaka and how it became the most important thing is his life. From his descriptions of finding the sci-fi club at college, skipping classes to read novels and debate them with his friends, attending his first sci-fi conventions, to eventually creating (with his friends) conventions of his own, Takeda's story is one that's all about the passion and creativity of the original Otaku Generation. For Takeda, that meant organizing clubs, projects, networks of friends, and events--all for fun, of course. One thing was made clear by Takeda's book: his genius and creativity manifest themselves in his networking abilities, his charisma, and his earnestness. As such, Takeda has always been involved in the business side of things at Gainax--day-to-day affairs, long-term strategy, partnerships, public relations, and whatnot.

There were two groups of important people in the very early days of Gainax: the organizers and the creators. On the creator side of things, we have some very familiar names: Hiroyuki Yamaga, Hideaki Anno, and Takami Akai. On the organizer side of things, we have: Toshio Okada, Takeshi Sawamura, and Yasuhiro Takeda. Gainax would not exist without both of these groups coming together to put on Daicon III and to create its now legendary opening animation. Toshio Okada, who was also with the company at the very beginning, has been the most publically visible of the organizers group, and he has talked about the history of Gainax before in lectures, interviews, etc. Okada, however, left the company in 1992 for reasons that are apparently somewhat in dispute. Takeshi Sawamura, who was around at the beginning but didn't join Gainax right away, was the individual held responsible for Gainax's tax evasion woes, and he left the company in 2000. That leaves Takeda, the only original Gainax board member still with the company.

There were two groups of important people in the very early days of Gainax: the organizers and the creators. On the creator side of things, we have some very familiar names: Hiroyuki Yamaga, Hideaki Anno, and Takami Akai. On the organizer side of things, we have: Toshio Okada, Takeshi Sawamura, and Yasuhiro Takeda. Gainax would not exist without both of these groups coming together to put on Daicon III and to create its now legendary opening animation. Toshio Okada, who was also with the company at the very beginning, has been the most publically visible of the organizers group, and he has talked about the history of Gainax before in lectures, interviews, etc. Okada, however, left the company in 1992 for reasons that are apparently somewhat in dispute. Takeshi Sawamura, who was around at the beginning but didn't join Gainax right away, was the individual held responsible for Gainax's tax evasion woes, and he left the company in 2000. That leaves Takeda, the only original Gainax board member still with the company.Having attended numerous anime conventions over the course of years, I've had the opportunity to see in person (and in some cases speak to) various members of Gainax, including Hideaki Anno, Hiroyuki Yamaga, Takami Akai, Yasuhiro Takeda, Yoshiyuki Sadamoto, Kazuya Tsurumaki, Hiroki Sato, and Toshio Okada. Of these, I found Yasuhiro Takeda to be the most friendly, open, and earnest of the bunch. Even though there are some conflicting accounts regarding some of the early Gainax and pre-Gainax happenings, I tend to trust Takeda at least a little bit more than the others. He doesn't seem to be the type who would lie, embellish, or exaggerate, and that makes him the perfect Gainax historian. In a company of anime creators who radiate rockstar auras, Yasuhiro Takeda seemed positively down-to-earth. I felt comfortable enough in his presence to ask him about his Wings of Honneamise necktie at FanimeCon 2003. (My friend James brazenly asked how much Gainax has to pay in taxes. Takeda answered candidly and with a sense of humor. Feigning (?) despair, he started writing a long string of zeroes on a napkin to illustrate the horribly large amount of money Gainax had to pay. James and I smiled, expressed our sympathies, and moved onto happier subjects.)

The strength of The Notenki Memoirs is Takeda's straight-shooting account of pre-Gainax and Gainax activities--an accounting of who was who, who did what, when, where, and why. The book includes an extensive set of notes to explain things further, and even a glossary of names to help keep track of who everyone is. What is lacking, however, is an in-depth account of the other side of the company, the wildly creative side. The book barely discusses artistic decisions at all. Descriptions of anime planning and production are very sparse indeed. In fact, if you haven't seen the entire body of Gainax's work pre-Evangelion, most of Takeda's discussion of anime will go right over your head since he doesn't describe the anime in much detail. That said, this book is meant for hardcore Gainax fans, people who love Otaku no Video as much as (or more than) Neon Genesis Evangelion. By the way, The Notenki Memoirs are an excellent accompaniment to Otaku no Video; they're kind of like extended liner notes.

The interview at the end with Takami Akai, Hideaki Anno, and Hiroyuki Yamaga was a nice addition, but it was solely for the purpose of their talking about Takeda, not about their own artistic motivations and the things that inspired them. Even though the book's cover features an Evangelion image, and the subtitle is "Studio Gainax and the Men Who Created Evangelion", The Notenki Memoirs is really not about Evangelion. Readers hoping for juicy details about where Anno got his ideas for the religious imagery in the series, or exactly what he was thinking when he made the final episodes and the movies, will be disappointed. What they will get instead is a sense of history and context. Who are these Gainax guys and where did they come from? What motivated them to become interested in anime and science fiction, and to get together to create amazing amateur works? How and why did they go professional? If you're interested in these questions, Takeda's book is for you.

Up until now, the history of Gainax in English has only been available through a handful of interviews and articles, most of them saying exactly the same few things, or in some cases contradicting each other. The Notenki Memoirs is now the most detailed and most authoritative recounting of Gainax's history in the English language. Being a Gainax fan, it was an absolute pleasure to read.

That said, it's not only Gainax otaku who will enjoy the book. Hardcore fans of anime in general will appreciate Takeda's story if only to read about people like themselves, and to be inspired by their success story. Takeda is an important figure in the Japanese science fiction convention scene, so anyone who is interested in fan convention culture, or who has ever had a good experience staffing a fan convention, will also like Takeda's book since a lot of time is spent detailing various events he has been involved with.

Coming in at 172 pages with relatively large text, The Notenki Memoirs is a very quick read. Information junkies, however, will enjoy the additional notes which are quite dense, and that doesn't even include the extra interview at the end of the book, a full timeline of events, and the bonus account of Takeda's hosting of the 2001 Japan Science Fiction Convention. My main complaint is that the book was lacking in illustrations; it only included a few small black and white photographs. (See the trivia and history sections of my Daicon website for more photos.) Nonetheless, with a retail price of $9.99, I thought the book was totally worth it. I highly recommended it.

The anime fandom documentary

The anime fandom documentary  Joe Doughrity, an anime fan and writer from Los Angeles, attended a Pop Japan Travel tour to Japan in 2004 and made a documentary about it called

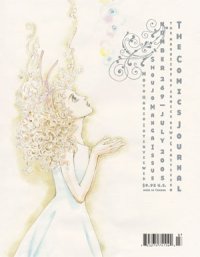

Joe Doughrity, an anime fan and writer from Los Angeles, attended a Pop Japan Travel tour to Japan in 2004 and made a documentary about it called  This isn't directly otaku-related, but those of you who have an academic interest in anime and manga might like to examine the latest issue of The Comics Journal. The July issue (#269), featuring beautiful cover art by Moto Hagio, focuses heavily on shoujo manga. It features reviews of shoujo manga, essays about shoujo manga, and an in-depth interview with Moto Hagio. For those of you who aren't so interested in shoujo, there's an interesting article about scanlations, and an article about manga and comic book shops.

This isn't directly otaku-related, but those of you who have an academic interest in anime and manga might like to examine the latest issue of The Comics Journal. The July issue (#269), featuring beautiful cover art by Moto Hagio, focuses heavily on shoujo manga. It features reviews of shoujo manga, essays about shoujo manga, and an in-depth interview with Moto Hagio. For those of you who aren't so interested in shoujo, there's an interesting article about scanlations, and an article about manga and comic book shops.

Awareness of otaku culture is very high right now in Japan due to a story called Densha Otoko which translates to "trainman". Supposedly a true story, Densha Otoko is about an otaku who saves a beautiful woman from a drunk on a train. She sends him a thank-you gift, and our poor otaku protagonist is interested in pursuing a relationship with the woman but is clueless on how to proceed. As such, he explains his plight on 2ch (ni-chaneru), an online bulletin board, and gets advice from his fellow otaku. The story was published as a best-selling book, and was recently made into a movie which hit #1 at the Japanese box office. There's even a manga. A few weeks ago, the Densha Otoko TV drama premiered, which I am currently in the process of watching. Some otaku will recognize the opening animation sequence of the TV show as being an homage to the Daicon IV Opening Animation, which you can read about here:

Awareness of otaku culture is very high right now in Japan due to a story called Densha Otoko which translates to "trainman". Supposedly a true story, Densha Otoko is about an otaku who saves a beautiful woman from a drunk on a train. She sends him a thank-you gift, and our poor otaku protagonist is interested in pursuing a relationship with the woman but is clueless on how to proceed. As such, he explains his plight on 2ch (ni-chaneru), an online bulletin board, and gets advice from his fellow otaku. The story was published as a best-selling book, and was recently made into a movie which hit #1 at the Japanese box office. There's even a manga. A few weeks ago, the Densha Otoko TV drama premiered, which I am currently in the process of watching. Some otaku will recognize the opening animation sequence of the TV show as being an homage to the Daicon IV Opening Animation, which you can read about here: